Convolution for optical broad-beam responses in scattering media

Photon transport theories, such as the Monte Carlo method, are commonly used to model light propagation in tissue. The responses to a pencil beam incident on a scattering medium are referred to as Green’s functions or impulse responses. Photon transport methods can be directly used to compute broad-beam responses by distributing photons over the cross section of the beam. However, convolution can be used in certain cases to improve computational efficiency.

Contents |

General convolution formulas

In order for convolution to be used to calculate a broad-beam response, a system must be time invariant, linear, and translation invariant. Time invariance implies that a photon beam delayed by a given time produces a response shifted by the same delay. Linearity indicates that a given response will increase by the same amount if the input is scaled and obeys the property of superposition. Translational invariance means that if a beam is shifted to a new location on the tissue surface, its response is also shifted in the same direction by the same distance. Here, only spatial convolution is considered.

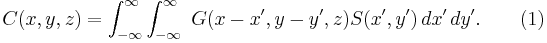

Responses from photon transport methods can be physical quantities such as absorption, fluence, reflectance, or transmittance. Given a specific physical quantity, G(x,y,z), from a pencil beam in Cartesian space and a collimated light source with beam profile S(x,y), a broad-beam response can be calculated using the following 2-D convolution formula:

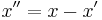

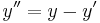

Similar to 1-D convolution, 2-D convolution is commutative between G and S with a change of variables  and

and  :

:

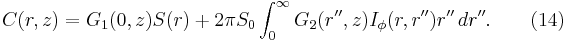

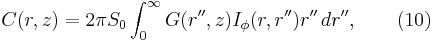

Because the broad-beam response  has cylindrical symmetry, its convolution integrals can be rewritten as:

has cylindrical symmetry, its convolution integrals can be rewritten as:

where  . Because the inner integration of Equation 4 is independent of z, it only needs to be calculated once for all depths. Thus this form of the broad-beam response is more computationally advantageous.

. Because the inner integration of Equation 4 is independent of z, it only needs to be calculated once for all depths. Thus this form of the broad-beam response is more computationally advantageous.

Common beam profiles

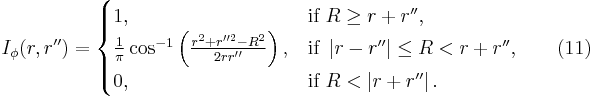

Gaussian beam

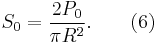

For a Gaussian beam, the intensity profile is given by

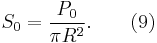

Here, R denotes the  radius of the beam, and S0 denotes the intensity at the center of the beam. S0 is related to the total power P0 by

radius of the beam, and S0 denotes the intensity at the center of the beam. S0 is related to the total power P0 by

Substituting Eq. 5 into Eq. 4, we obtain

where I0 is the zeroth-order modified Bessel function.

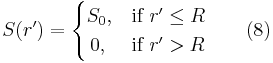

Top-hat beam

For a top-hat beam of radius R, the source function becomes

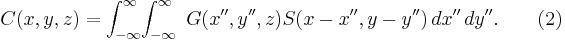

where S0 denotes the intensity inside the beam. S0 is related to the total beam power P0 by

Substituting Eq. 8 into Eq. 4, we obtain

where

Errors in numerical evaluation

First interactions

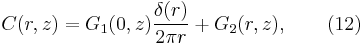

First photon-tissue interactions always occur on the z axis and hence contribute to the specific absorption or related physical quantities as a delta function. Errors will result if absorption due to the first interactions is not recorded separately from absorption due to subsequent interactions. The total impulse response can be expressed in two parts:

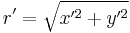

where the first term results from the first interactions and the second, from subsequent interactions. For a Gaussian beam, we have

For a top-hat beam, we have

Truncation error

For a top-hat beam, the upper integration limits may be bounded by rmax, such that r ≤ rmax − R. Thus, the limited grid coverage in the r direction does not affect the convolution. To convolve reliably for physical quantities at r in response to a top-hat beam, we must ensure that rmax in photon transport methods is large enough that r ≤ rmax − R holds. For a Gaussian beam, no simple upper integration limits exist because it theoretically extends to infinity. At r >> R, a Gaussian beam and a top-hat beam of the same R and S0 have comparable convolution results. Therefore, r ≤ rmax − R can be used approximately for Gaussian beams as well.

Implementation of convolution

There are two common methods used to implement discrete convolution: the definition of convolution and fast Fourier transformation (FFT and IFFT) according to the convolution theorem. To calculate the optical broad-beam response, the impulse response of a pencil beam is convolved with the beam function. As shown by Equation 4, this is a 2-D convolution. To calculate the response of a light beam on a plane perpendicular to the z axis, the beam function (represented by a b × b matrix) is convolved with the impulse response on that plane (represented by an a × a matrix). Normally a is greater than b. The calculation efficiency of these two methods depends largely on b, the size of the light beam.

In direct convolution, the solution matrix is of the size (a + b − 1) × (a + b − 1). The calculation of each of these elements (except those near boundaries) includes b × b multiplications and b × b − 1 additions, so the time complexity is O[(a + b)2b2]. Using the FFT method, the major steps are the FFT and IFFT of (a + b − 1) × (a + b − 1) matrices, so the time complexity is O[(a + b)2 log(a + b)]. Comparing O[(a + b)2b2] and O[(a + b)2 log(a + b)], it is apparent that direct convolution will be faster if b is much smaller than a, but the FFT method will be faster if b is relatively large.

Computational examples

The fate of photons can be modeled using a Matlab implementation of the Monte Carlo method (nrel = 1, μa = 0.1, μs=100, g = 0.9, 100,000 photons). Using this Matlab model, the fluence of a 3 × 3 × 3 cm3 region is recorded and the fluence distribution of a broad-beam response is plotted. Figure 1 and Figure 2 show the responses to a pencil beam and a 1-cm top-hat broad-beam, respectively. Direct convolution was used to calculate the broad-beam response in Figure 2. Figure 3 shows the broad-beam response calculated using the FFT method. When the diameter of the light beam is 0.2 cm, direct convolution costs 1.93 seconds, and the FFT method costs 7.35 seconds. When the diameter of the light beam is 2 cm, direct convolution costs 90.1 seconds, and FFT method costs 16.8 seconds. Of course, the absolute computation time depends on the processing speed of the computer being used. These two comparisons were made on the same computer. Although the computation times differ, the plots in Figures 2 and 3 are indistinguishable.

See also

- Radiative transfer equation and diffusion theory for photon transport in biological tissue

- Monte Carlo method

- Monte Carlo method for photon transport

Links to other Monte Carlo resources

References

- L.-H. Wang and H.-I. Wu. Biomedical Optics: Principles and Imaging. Wiley 2007.

- L.-H. Wang, S. L. Jacques, and L.-Q. Zheng, "Monte Carlo modeling of photon transport in multi-layered tissues," Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine 47, 131–146 (1995).

- L.-H. Wang, S. L. Jacques, and L.-Q. Zheng, "Convolution for responses to a finite diameter photon beam incident on multi-layered tissues," Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine 54, 141–150 (1997). Download article.

![C(r,z) = \int_0^\infty \ S(r')r' \left [ \int_{0}^{2\pi} \ G\left (\sqrt{r^2%2Br'\,^2-2rr'cos\phi'},z \right )\, d\phi' \right ]dr' \qquad(3)](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/6d97f9ca72eeb16700ec66c3304e559a.png)

![C(r,z)=\int_0^\infty G(r'',z)r'' \left [ \int_{0}^{2\pi} S \left ( \sqrt{r^2%2Br''\,^2-2rr''cos\phi''} \right ) \, d\phi'' \right ]dr''\qquad(4)](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/00ba65017fd8a4053f9dbe6c3982d338.png)

![S(r') = S_0 \exp \left [ -2 \left( \frac{r'}{R} \right )^2 \right]. \qquad(5)](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/7835db846b518372069e9b0faf7cd371.png)

![C(r,z) = 2\pi S(r)\int_{0}^{\infty} G(r'',z)\exp\left [-2\left (\frac{r''}{R} \right )^2 \right ]I_0\left (\frac{4rr''}{R^2} \right ) r'' \, dr'', \qquad(7)](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/24189eebcd52dc335785bb5f0f4279c9.png)

![C(r,z)=G_1(0,z)S(r)%2B2\pi S_0\int_{0}^{\infty} G_2(r'',z)\,exp\left [-2\left (\frac{r''-r}{R} \right )^2 \right ]I_{0e}\left(\frac{4rr''}{R^2} \right )r''\,dr''.\qquad(13)](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/3b176417f9539e468d0845584803d2ad.png)